Granular bio-organic fertilizer uses agricultural waste as raw material, incorporating beneficial microbial communities, and is processed through scientific techniques. It has the effects of enriching the soil, improving fertility, and improving the ecosystem. Its production process is rigorous and orderly, mainly divided into five core stages: raw material pretreatment, fermentation and maturation, granulation, drying and cooling, and finished product inspection and packaging. Each step directly affects product quality.

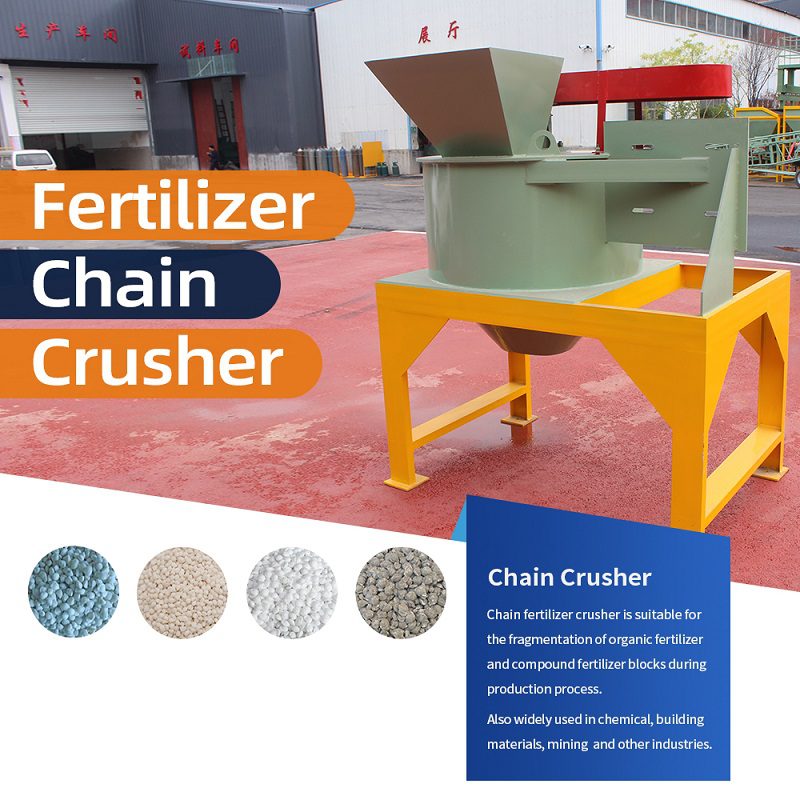

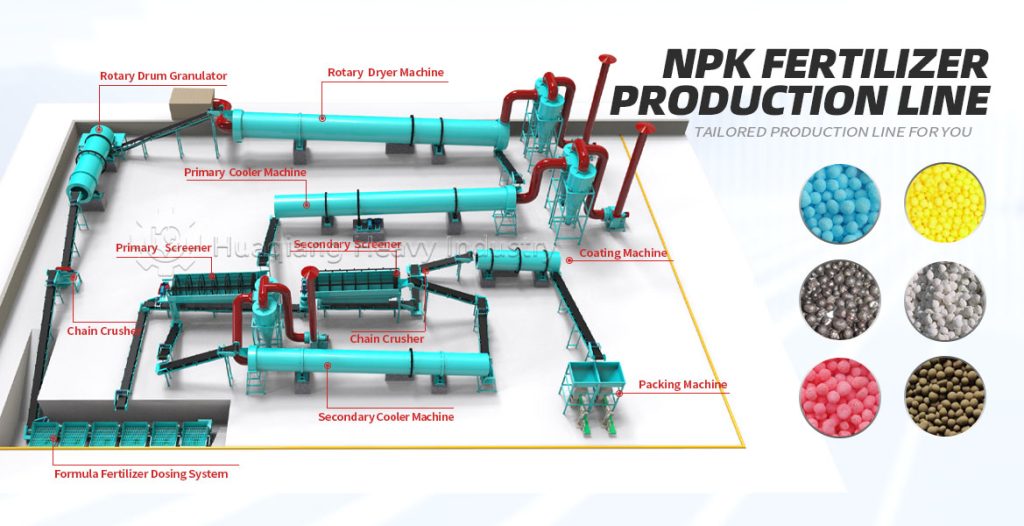

Raw material pretreatment is the foundation of production. Workers first screen raw materials such as livestock and poultry manure, straw, bamboo residue, and coal ash, removing impurities such as stones and plastics. Then, using crushing equipment, straw and bamboo residue are processed into short fibers of 1-1.5mm, and coal ash is crushed to 70-150 mesh, ensuring the raw materials are uniform and fine, laying the foundation for subsequent fermentation and granulation. At the same time, the raw materials are mixed according to a scientific ratio, adjusting the moisture content and carbon-nitrogen ratio to make the materials more suitable for microbial reproduction.

Fermentation and maturation is the core stage, determining the fertilizer’s efficacy and safety. The mixed raw materials are fed into a sealed fermentation tank or fermentation vessel, inoculated with functional microbial agents, and the temperature is controlled at 55-65℃ and maintained for at least 5 days. This kills harmful bacteria and promotes the decomposition of organic matter by microorganisms. During fermentation, a compost turning machine is needed to regularly turn the compost pile to provide oxygen and ensure uniform decomposition. Generally, fermentation takes 7-15 days, followed by 7 days of aging to obtain thoroughly decomposed, odorless organic material.

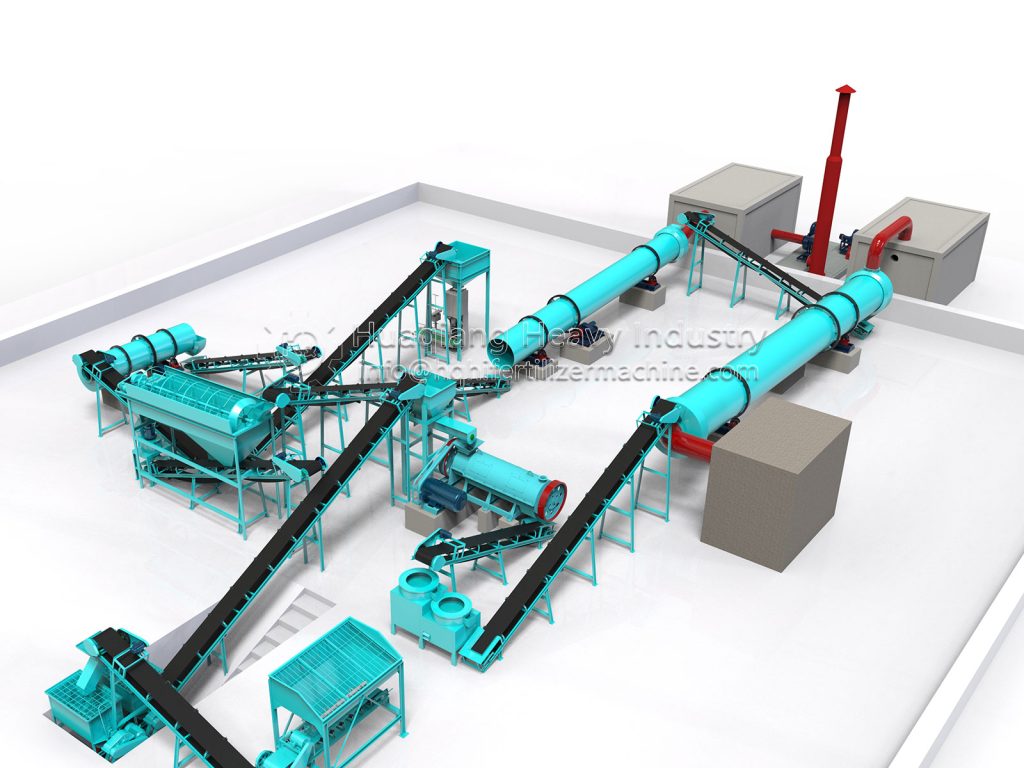

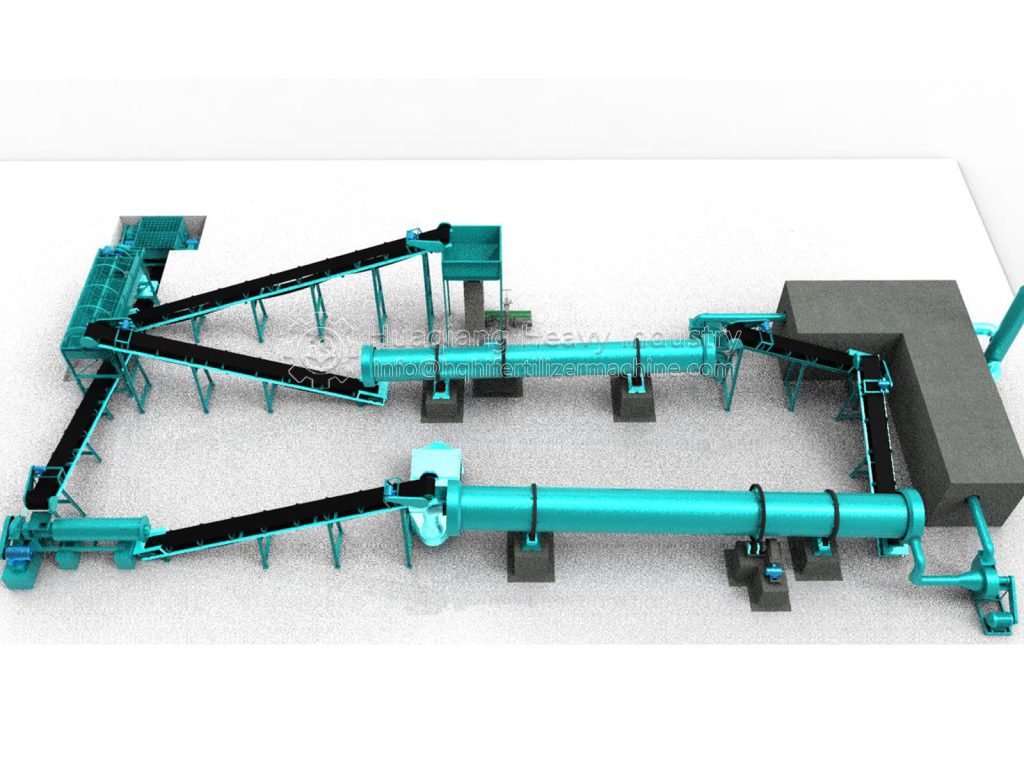

Granulation is the key to achieving the desired granule shape. The appropriate process is selected based on the production scale. Small and medium-sized production lines often use disc granulators, utilizing centrifugal force and gravity to roll and agglomerate the material. Large-scale production uses new type organic fertilizer granulators, relying on intelligent control and structural optimization to form dense granules through extrusion molding, offering wider adaptability and better granulation results. During granulation, an appropriate amount of binder can be added to adjust the particle size to 2-8mm, ensuring roundness and strength, maintaining a granulation rate of over 80%, which is more environmentally friendly and efficient than traditional equipment.

Drying, cooling, inspection, and packaging are the final steps to ensure product stability. The formed granules are fed into a dryer, with the temperature controlled at 70-80℃ to reduce the moisture content to below 15%, preventing mold growth. They are then cooled in a cooler to prevent clumping. After cooling, the granules are sieved to remove substandard products, and then undergo inspection and testing to confirm that indicators such as fertilizer efficacy and microbial content meet standards. Finally, they are quantitatively packaged, labeled, and stored.

The entire bio-organic fertilizer production process balances environmental protection and high efficiency, realizing the resource utilization of agricultural waste while locking in fertilizer efficacy through scientific processes. A standardized production process is a crucial guarantee for granular bio-organic fertilizer to effectively improve soil and promote crop growth, and it also provides strong support for the development of green agriculture.